Born in France to American parents, Nicole Eisenman graduated from the Rhode Island School of Design in 1987. The inspiration for her works comes from the allegorical paintings of ancient art (Rubens), but also from popular culture (comic strips, advertisements, TV series and B-movies), with a special debt to the draughtsman Robert Crumb: the host of figures which are the hallmark of her works plunges us into vaguely familiar cosmology. But the satirical realism of certain gigantic drawings also echoes the wall frescoes of the Works Progress Administration on the 1930s, an agency set up as part of the New Deal, which commissioned artists to produce large decorative projects. Last of all, her style as well the spirit of social criticism which typifies her work borrow from German Expressionism.

With its variable style, her work stems from satire as much as from re-appropriation. In this revision of art history, the artist shifts elements coming from well-known works into a lesbian punk environment and a grotesque and hallucinatory atmosphere. Through the irony she makes use of, she is close to contemporary artists like John Currin, and German painters in the Leipzig school, but she suggests a re-think of the macho conventions of the predominant iconography thanks to her objects with powerful sexual connotations, which release a merry vulgarity. Her world is filled with orgiastic crowds, dionysiac sacrifices, and allegorical and heroic scenes where the main roles are played by women. Mythical figures leave their roles and undertake bold acts of vengeance, like the Amazons chasing Minotaur by Pablo Picasso, with an overtly aggressive and fun-loving libido, well removed from any norms (The Minotaur Hunt, 1992). Among her most recent works, the theme of lesbian motherhood stands out. She also produces portraits imbued with sadness, which she contrasts with an obsession with happiness [1].

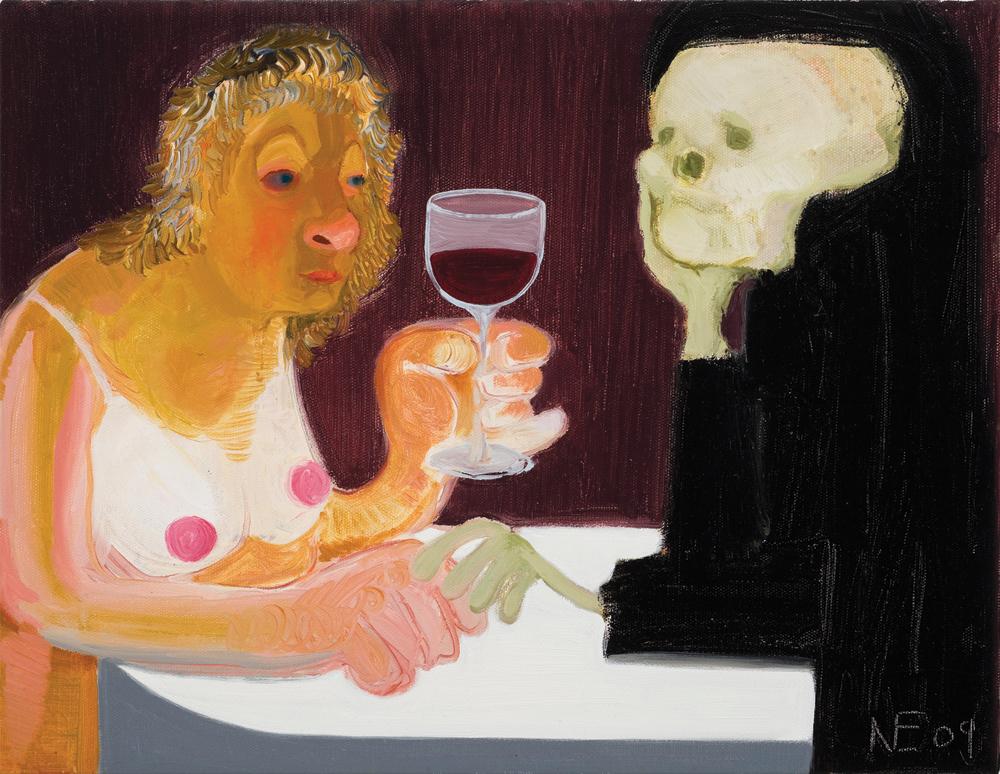

Nicole Eisenman, Death and the Maiden, 2009, oil on canvas, 548 x 426 cm. Collection of Martin and Rebecca Eisenberg.

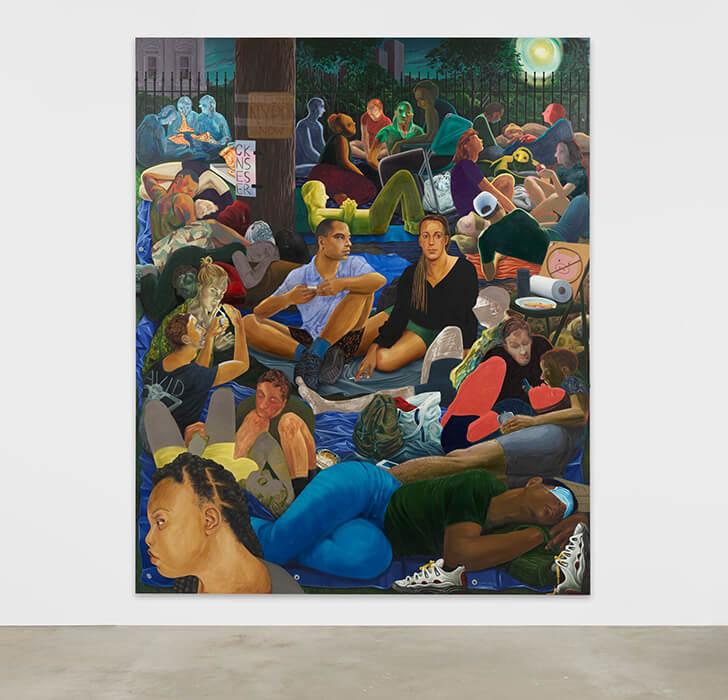

The vivid and odd images of the American artist Nicole Eisenman are familiar to anyone who follows her rich and long career. Crazy farmers, fools, fantasizers, clowns, artists, coaches, bohemians, zoomorphs, strangers, beer drinkers, jumpers, sisters, gropers, tea-partiers, sailors, girls, superheroes, birds, neighbours, monkeys, asses, nudes, dancers, cats, friends, paranormals, fanatics and stripped-bare maidens and other colorful characters that excite the mind of a decent mom. They scream and rage on the canvases, break out into the silence of the sterile gallery space, appealing to the neo-expressionism of the 1980s and its father, Edvard Munch [2].

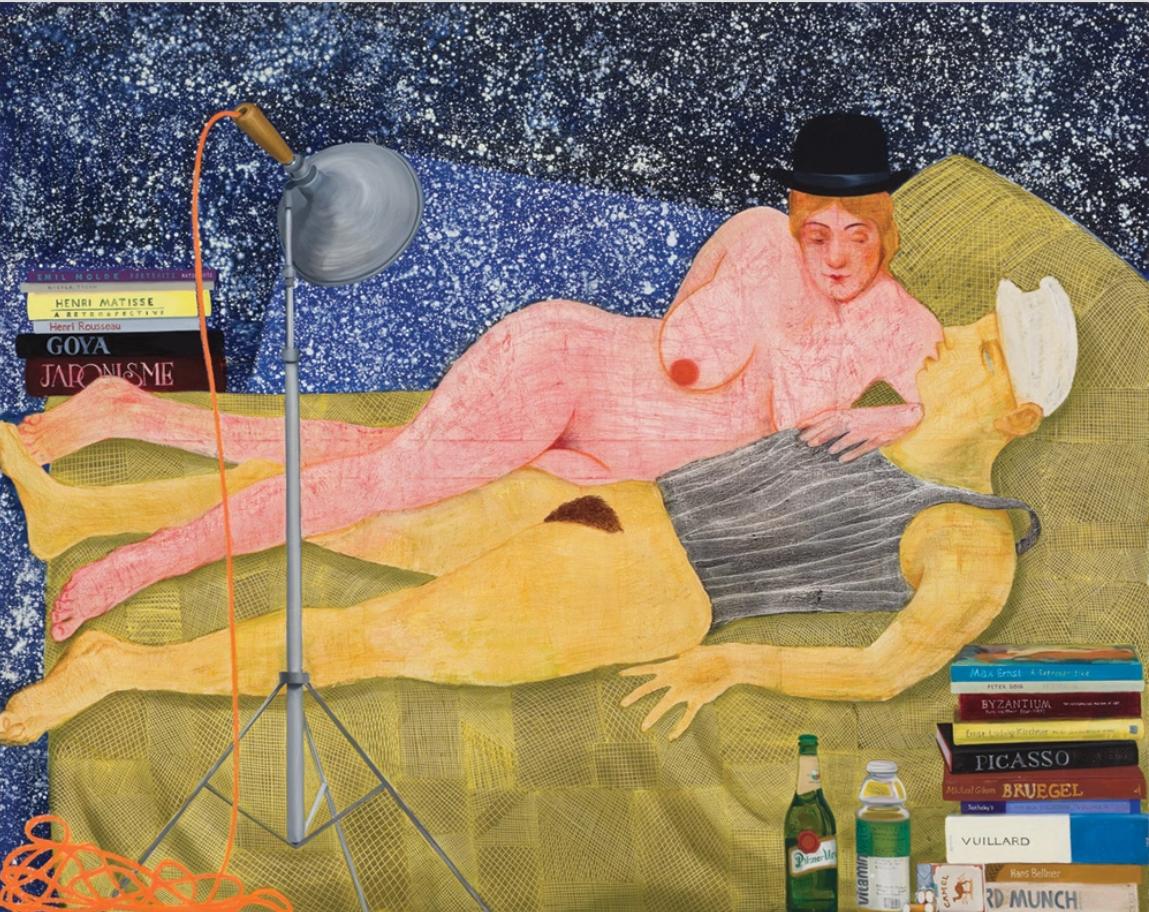

Nicole Eisenman: Night Studio, 2009, oil on canvas, approx. 167 x 201 cm; at the New Museum.

Perhaps a little comparison of two dinner paintings will illuminate here: Sunday Dinner by Eisenman and The Wedding of the Bohemian (1925) by Edvard Munch. In Eisenman’s Sunday Dinner, the guest of honor, in full Sharon Stone exposure, takes on the male gaze. We’re sexual beings and oglers. What is the urban legend? A sexual thought every seven seconds for males. For a more valid, yet still hearty number on this, we could defer to a study done on Ohio State University College students published in the January 2012 issue of the Journal of Sex Research. The median number of times per day men in the test group thought about sex was 19, as compared to 10 for women. In Sunday Night Dinner, more than meatballs are being devoured in this strange presentation that recalls and amplifies Manet’s mischief with the same motif. Munch also places a woman (in this case a bride) at the center of dour behavior that is strange, considering that it should be a happy occasion. Like Eisenman, there is both male and female angst, but without license to goof around. In Munch’s expressionism, anxiety, jealousy, sex, death and all the other usual suspects were not exactly big laughs. And that seemed just about right for Munch. His genius rose elsewhere.

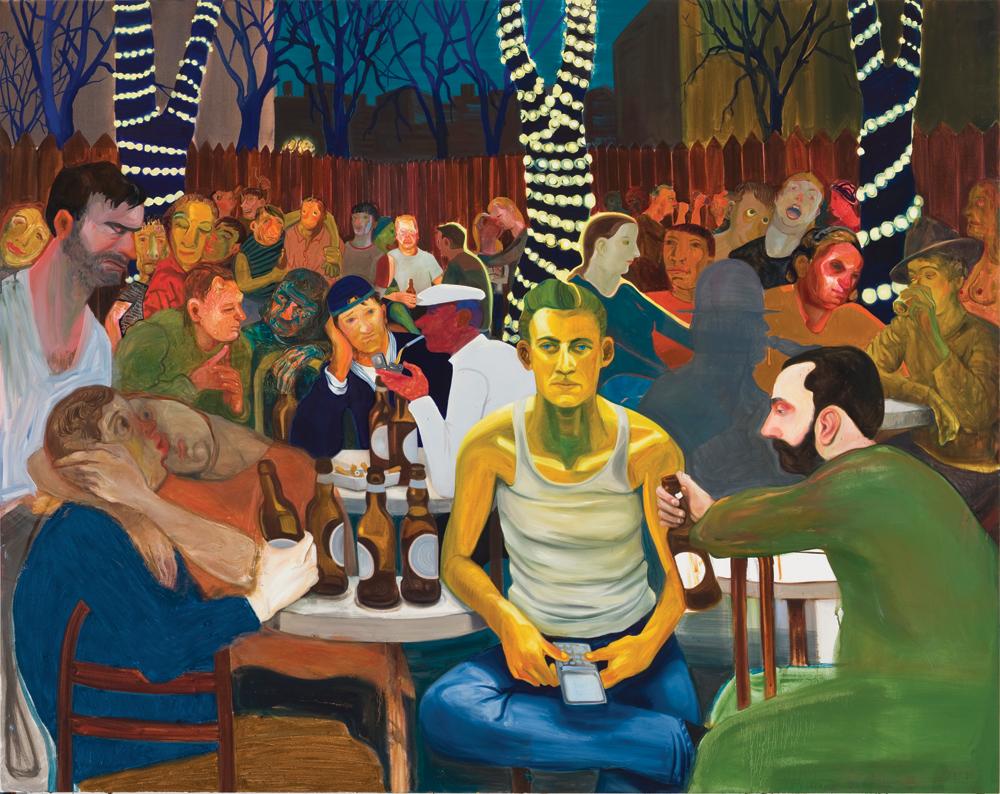

Nicole Eisenman, Beer Garden with Ash, 2009, oil on canvas. Private collection, Switzerland.

Eisenman and Munch start to correlate again, though, when we consider at formal qualities. Both compositions have excellent design and place viewers right at the table. Both works have heightened color, visceral scrubbing and reliance on line to do a lot of the work. Eisenman does conjure up a bit more of Van Gogh than Munch does, especially in her foreground figure sipping wine. For the quirky, devilish figure (lower far-right corner), she slaps down thick paint and gouges into it with the brush handle. Munch used the brush handle and thick paint at times as well, but in other paintings. If you can not make it to the Carnegie International, aim for the much larger survey of Eisenman’s work: “Dear Nemesis,” at the Contemporary Art Museum in St. Louis, the largest collection of her work to date, with more than 120 paintings, prints and drawings from the 1990s to the present. The Triumph of Poverty is one of the best inclusions in the exhibition, which runs from Jan. 24 through April 13. Eisenman’s sociopolitical angst is vented in works such as The Triumph of Poverty, a history painting that delivers an indictment against the worldwide economic crisis that peaked in 2008—a 21st-century Grapes of Wrath.

Nicole Eisenman, American Goth, 2018, Stainless steel and paper pulp, Dimensions Variable.

But what makes this a memorable painting is the unpredictable composition. For example, look at the ring of five hands in the center of the composition and notice how everything spins out from there, with the diminishing of figures in all directions. Relative sizes break logic in service to composition and the sensation of the strange world 50 laps can put the mind in. The composition delivers a sort of a Petri dish of human interaction, both sexual and social. Eisenman is in the vanguard of 21st-century Expressionists that overlay Edvard Munch, James Ensor and the German expressionists Max Beckmann, George Grosz, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner and Otto Dix. And the list goes on. However, Eisenman is much better, in a Robert Hughes kind of measure, than 1980s Neo -Expressionism, at least the kind that reigned over most the art market that decade. Not all, but a lot of that “bad” painting that was so exalted at the time has turned out to be just Bad—in a what-were-we-thinking kind of way. In this mostly male dominium, the worst offenders were David Salle and Julian Schnabel. The late art critic Robert Hughes, though, was never a believer in it. He was turned off by the lack of technical skill, as well as the inability to draw the figure, and construct a decent composition. He said of such painters “I don’t like art that thinks it is enough to quote the high achievements of the past—that pretends to be heavy and then takes itself lightly. It merely puts you in a kind of free-floating zone” [3]

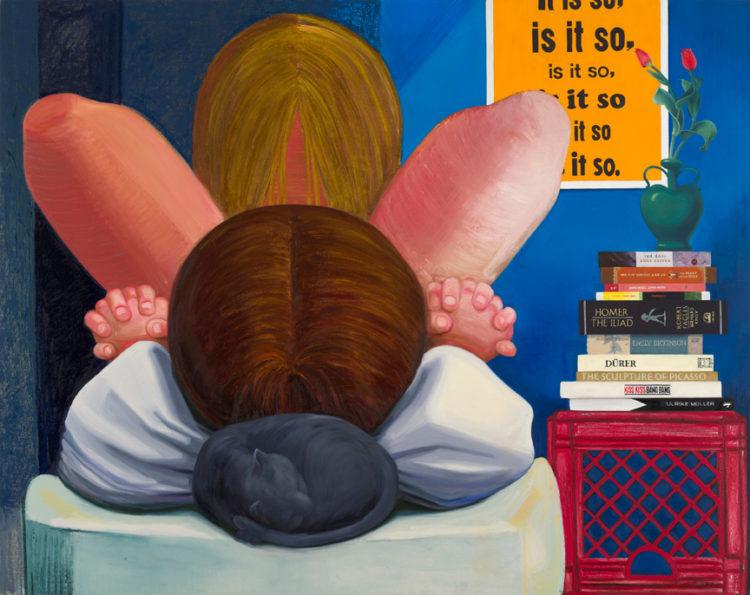

Nicole Eisenman, It Is So, 2014, oil on canvas, 165.1 x 208.3 cm, 65 x 82 in., Courtesy Anton Kern Gallery, New York and Susanne Vielmetter Los Angeles Projects

Hughes’ 1980s argument proved itself overtime. Consider the forgetfulness that museums have regarding Neo-Expressionism. In a February Art in America essay last year, “Neo-Expressionism Not Remembered,” Raphael Rubenstein reminded us that the last time we saw a “big show” by a “Neo-Ex star” in a New York museum was Francesco Clemente’s Guggenheim retrospective in 1999. But the 1980s Neo-Expressionism had bright spots, and even Hughes held a little more regard for Eric Fischl [4].

Gems like Fischl’s Old Man’s Boat Old Man‘s Dog (1985) are not so easily dismissed. In addition, Hughes had high regard for peripheral figures: Susan Rothenberg for one. Arthur Danto recalled the exuberance of the period in observing that Neo-Expressionism brought with it a joy that figure painting was back, and he aptly recalled that the “Inaugural exhibition of the redesigned Museum of Modern Art in 1984 made it appear as if Neo-Expressionism was a worldwide phenomenon” [5].

Eisenman‘s work is respectful to its early 20th-century roots by not making formal aspects of painting into a joke. She mixes in 1920’s formal debauchery into her strong compositions and skill in rendering. It comes down to the old but useful cliché: Knowing how to draw informs good distortion.

Stephen Knudsen in interview asked Eisenman for the meaning of the title of her upcoming CAM St. Louis show, Dear Nemesis. And he thinks, that Eisenman’s words are a good way to go out: “Nemesis is the Greek god of retribution, specifically for the crime of indiscretion, of hubris. If you start to think you’re a god, she’s the one who will put you in your place. Maybe she pays extra attention to artists, since it is our job to create something out of nothing.” It is Nemesis who steps in and introduces the struggle into the process.

The last Nicole Eisenman’s Solo Show, called ‘Untitled (Show)’ celebrates the interplay between painting and sculpture in their restless, expansive practice. It is their first major solo exhibition at Hauser & Wirth New York, spanning two floors of the gallery’s building on West 22nd.

If ‘Untitled’ is a show about what Eisenman has been doing for two or three years, it is also a show – the clearest demonstration yet – of what they have been doing for three decades: building a world where life and form can finally have it out.

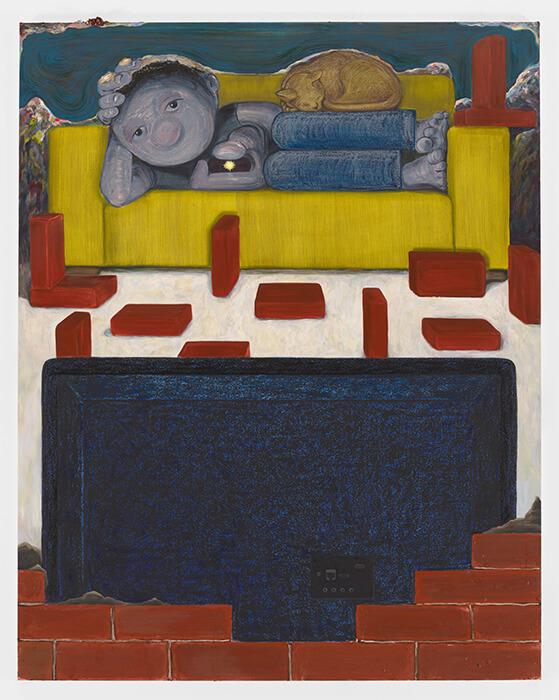

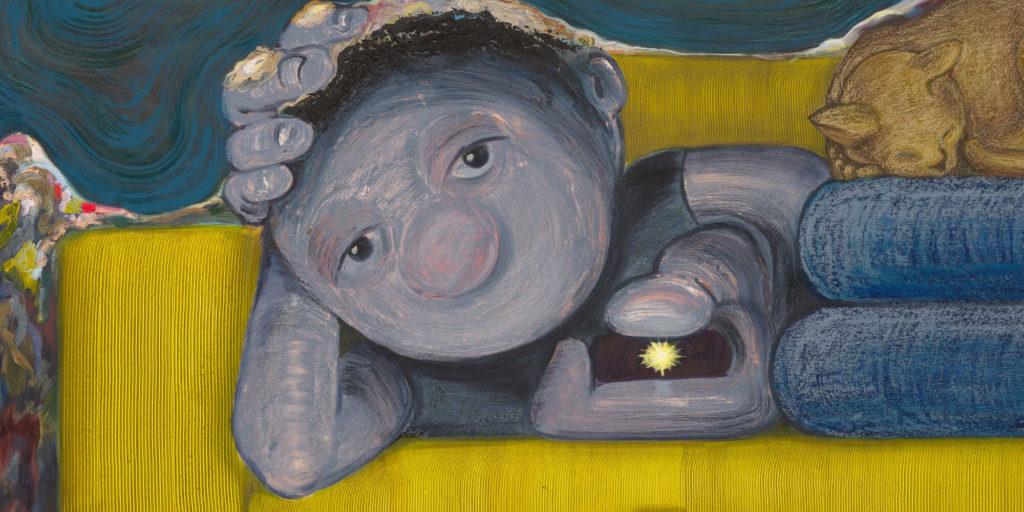

Nicole Eisenman, Reality Show (details), 2022.

At the heart of the exhibition is ‘Maker’s Muck’ (2022), a representation of the creative process that is thoroughly evolutionary in spirit. An outsized plaster figure sits hunched over a potter’s wheel, on which a mound of ersatz clay interminably spins. The floor teems with sculptures. Some of the pieces are fully rendered and recognizable: owl, kouros, ketchup bottle. Others are either unfinished or beyond done, i.e. abstracted. A few are still little lumps. (Evolution is not in fact linear.)

Constructivist rigor marks out the newest paintings in the show. A lone figure – perhaps no figure in Eisenman’s oeuvre has been as lone – in ‘The Ledge’ (2022) looks less like a body than like a walking (not talking) stick. The black box that makes up the whole of the foreground in ‘Reality Show’ (2022) is what some people call a television; it is also what B.F. Skinner called the human mind. Synecdoche serves this artist well: ‘When you can’t think of what to draw,’ they’ve said, ‘draw a head.’ Meaning: the head stands in for the thought. Or vice versa? Eisenman’s heads are getting bigger [6].

The interacting spectator can find the end of his story in the head of the Eisenman, which is known for such collaborations.

- Fabienne Dumont , translated by Simon Pleasance: The Dictionnaire universel des créatrices, 2013 // https://awarewomenartists.com/en/artiste/nicole-eisenman/

- Knudsen S. Nicole Eisenman: The Relevance of 21st-Century Expressionism: Artpulse Magazine, 2013. // http://artpulsemagazine.com/nicole-eisenman-the-relevance-of-21st-century-expressionism /

- Boynton, Robert S., The Lives of Robert Hughes: The New Yorker, May 12, 1997.

- Knudsen S. Beyond Postmodernism/”Putting a Face on Metamodernism without the Easy Clichés”, Artpulse Magazine, No. 14, Winter 2013

- Danto, Arthur C., Unnatural Wonders / Essays from the Gap Between Art and Life. New York: Columbia University Press, 2007, p. 16.

- From exhibition profile at Hauser & Wirth gallery // https://vip-hauserwirth.com/gallery-exhibitions/nicole-eisenman-untitled-show/